Meta Platforms, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, is under intense scrutiny following revelations that it earned billions from fraudulent advertising. A Reuters investigation published in November 2025 revealed that Meta projected 10% of its 2024 revenue — about $16 billion — came directly from scam ads. These ads include fake investment schemes, counterfeit goods, illegal gambling, and banned medical products. The findings have sparked outrage among lawmakers, regulators, and consumer advocates, who argue that Meta has knowingly allowed fraud to flourish on its platforms in pursuit of profit.

This is not a story about isolated bad actors slipping through the cracks. It is about a system that appears to have been designed to maximize revenue, even when that revenue came from deception and exploitation. The scale of the problem raises urgent questions about corporate responsibility, regulatory oversight, and the future of trust in digital platforms.

The Scale of the Problem

The internal documents reviewed by Reuters paint a staggering picture of how deeply fraudulent advertising has penetrated Meta’s ecosystem. Meta’s platforms reportedly delivered 15 billion scam ads per day in 2024. These ads were not fringe anomalies; they were a significant part of the company’s revenue stream.

The types of scams were diverse and deliberately targeted. Fake investment opportunities promised unrealistic returns, often using doctored celebrity endorsements to lure victims. Illegal gambling operations preyed on vulnerable users, while counterfeit goods were marketed as luxury items, exploiting consumer desire for status at a lower price. Banned medical products, including miracle cures and unregulated supplements, were pushed to users desperate for health solutions.

In the United Kingdom alone, Meta allegedly earned £600 million from fraudulent ads in 2024, a figure that surpasses the combined digital advertising revenue of the country’s entire news industry. In the United States, lawmakers estimate that Meta’s platforms were implicated in a third of all scams nationwide, contributing to more than $50 billion in consumer losses last year.

Meta’s Response — and the Growing Public Skepticism

In a statement to Reuters, Meta spokesman Andy Stone said the documents “present a selective view that distorts Meta’s approach to fraud and scams.” He argued that the internal estimate was “rough and overly-inclusive” because it counted “many” legitimate ads as well. Stone claimed the true number was lower but declined to provide an updated figure.

Meta also pointed to a 58% reduction in scam reports over 18 months, insisting it “aggressively” addresses fraud. Critics, however, argue that the company’s own internal projections contradict its public narrative, showing billions in ongoing fraudulent impressions.

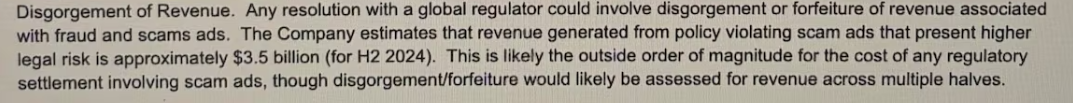

An excerpt from a November 2024 strategy document discussing Meta’s scam ad revenue and legal risks further illustrates the disconnect between Meta’s public messaging and its internal data. (Screenshot via REUTERS):

What the Reuters Investigation Reveals About Meta’s Internal Culture

The Reuters reporting goes far beyond surface-level numbers. The documents they reviewed paint a picture of a company that understood the scale of the fraud problem — and repeatedly chose not to meaningfully address it. According to the investigation, Meta’s internal teams had been tracking scam-related revenue for years, producing detailed projections, risk assessments, and warnings that never made it into public transparency reports.

One internal analysis described scam ads as a “persistent, high-volume revenue source,” noting that enforcement efforts were “insufficient to meaningfully reduce exposure.” Another document acknowledged that Meta’s automated systems approved large volumes of fraudulent ads because tightening the filters would “significantly impact advertiser throughput.”

In other words: Meta knew the system was broken, but fixing it would cost money.

Internal Teams Flagged the Problem — Leadership Minimized It

Reuters reported that multiple internal teams — including integrity researchers, policy analysts, and risk specialists — raised alarms about the scale of fraudulent advertising. These warnings included:

- projections showing billions in annual scam-related impressions

- internal dashboards tracking high-risk ad categories

- reports showing that scam advertisers were among the highest spenders

- risk memos warning of regulatory exposure in the EU, UK, and US

Yet leadership often downplayed these findings, framing them as “overestimates,” “methodological noise,” or “not reflective of real-world harm.” This internal minimization is a recurring theme: employees flag the problem, leadership reframes it, and the system continues unchanged.

A Pattern of Public Messaging That Doesn’t Match Internal Data

One of the most striking elements of the Reuters investigation is the gap between Meta’s public statements and its internal numbers.

Publicly, Meta insists that scam ads represent a tiny fraction of its advertising ecosystem. Internally, however, the company tracked:

- 15 billion scam impressions per day

- 10% of annual revenue tied to fraudulent ads

- major spikes in scam activity during global crises

- repeat offenders who evaded enforcement dozens of times

Reuters highlighted this discrepancy as a core issue: Meta’s public narrative emphasizes safety and integrity, while its internal data shows a system overwhelmed by fraud.

A System Built to Reward Bad Actors

The internal documents suggest that fraudulent advertising wasn’t just slipping through the cracks — it was thriving in an environment that rewarded speed, scale, and revenue above all else. Meta’s ad infrastructure is designed to approve and deliver ads in seconds, prioritizing volume over verification. That design choice created the perfect conditions for scammers to operate at industrial scale.

Fraudsters learned quickly that Meta’s automated review systems could be gamed with minor tweaks: swapping a domain, altering a logo, or using AI-generated faces to evade detection. When one account was banned, another could be created within minutes. Internal teams repeatedly warned leadership that the platform’s architecture made it “easy to abuse and hard to police,” but meaningful structural changes were rarely implemented.

The Human Cost Hidden Behind the Metrics

While Meta framed the issue in terms of percentages and projections, the real-world impact was devastating. Scam ads on Meta’s platforms have been linked to:

- wiped-out retirement accounts

- identity theft

- fraudulent crypto investments

- counterfeit medication injuries

- small businesses losing thousands to fake “business services”

- vulnerable users being targeted repeatedly after a single click

One internal report acknowledged that scam victims often clicked on multiple fraudulent ads in a short period, creating a feedback loop where Meta’s algorithm interpreted their desperation as “interest” and served them even more harmful content.

Warnings Meta Ignored

The documents also show that Meta was repeatedly alerted to the severity of the problem:

- internal researchers flagged “catastrophic levels of fraud”

- policy teams warned that enforcement tools were “insufficient and easily bypassed”

- engineers noted that scammers were outpacing detection systems

- regional teams reported spikes in complaints not reflected in public reports

Despite these warnings, Meta continued to emphasize revenue growth and advertiser volume in internal performance metrics. Attempts to tighten enforcement were often met with resistance because they risked reducing ad revenue.

A Global Problem With Local Consequences

Fraud on Meta’s platforms is not evenly distributed. The documents show that scammers disproportionately targeted:

- older adults

- immigrants

- low-income users

- people searching for medical or financial help

- users in countries with weaker consumer-protection laws

In some regions, fraudulent ads made up such a large share of Meta’s ads inventory that local regulators described the platform as “a public safety hazard.”

The Ethical Question: What Does Meta Owe Its Users?

The Reuters investigation forces a deeper question that goes beyond revenue charts, enforcement failures, or PR statements: What ethical responsibility does a platform of Meta’s size have to the people who use it?

Meta’s business model is built on trust — trust that the ads users see are legitimate, trust that the platform will protect them from harm, and trust that the company’s public commitments reflect its internal priorities. But the documents reviewed by Reuters show a company that repeatedly prioritized revenue over safety, even when internal teams warned that users were being systemically exploited.

At its core, the ethical issue is simple: If a company profits from fraud, knowingly or through negligence, is it still a neutral platform — or is it a participant?

Meta’s internal projections suggest that scam advertisers were not an occasional nuisance but a dependable revenue stream. When a platform earns billions from fraudulent ads, the line between hosting harm and enabling harm becomes dangerously thin.

The ethical stakes are enormous. Meta’s decisions affect billions of people, many of whom lack the digital literacy, financial stability, or support systems to navigate sophisticated online scams. Vulnerable users — older adults, immigrants, people in crisis — are often the ones who pay the highest price.

The question is no longer whether Meta can detect fraud. It’s whether Meta is willing to sacrifice profit to protect the people who trust it.

Where This Leaves Us Now

The Reuters investigation doesn’t just expose a technical failure or policy gap — it reveals a structural flaw in the way modern digital platforms operate. When a company’s revenue depends on the volume of ads it delivers, even fraudulent ones, the incentives will always tilt toward growth over safety.

Meta’s internal documents show a company that understood the scale of the problem, tracked it, quantified it, and still allowed it to continue. The harm was not abstract. It was measurable, predictable, and preventable.

That leaves us with a sobering reality: If a platform this large can profit from fraud at this scale, what does that mean for the future of online trust?

The digital world is built on invisible systems — algorithms, ad networks, automated approvals — that most users never see. When those systems fail, the consequences fall on ordinary people, not the corporations that built them.

The Reuters investigation is a reminder that transparency is not a luxury. It is a necessity. Without it, platforms can quietly become engines of exploitation while presenting themselves as guardians of safety.

Meta’s response to these revelations will shape more than its reputation. It will shape the future of digital accountability, the expectations we place on tech giants, and the standards we demand from the platforms that mediate our lives.

Because if billions can be made from fraud in plain sight, the question isn’t just what Meta will do next — it’s what we, as a society, are willing to tolerate.

By Beth Gibbons (Queen of Karma)

Beth Gibbons, known publicly as Queen of Karma, is a whistleblower and anti-MLM advocate who shares her personal experiences of being manipulated and financially harmed by multi-level marketing schemes. She writes and speaks candidly about the emotional and psychological toll these so-called “business opportunities” take on vulnerable individuals, especially women. Beth positions herself as a survivor-turned-activist, exposing MLMs as commercial cults and highlighting the cult-like tactics used to recruit, control, and silence members.

She has contributed blogs and participated in video interviews under the name Queen of Karma, often blending personal storytelling with direct confrontation of scammy business models. Her work aligns closely with scam awareness efforts, and she’s part of a growing community of voices pushing back against MLM exploitation, gaslighting, and financial abuse.

Leave A Comment