Religion is not a single invention but a mosaic of practices, rituals, and stories that emerged gradually as humans tried to make sense of their world.

To ask what the “first religion” was is to step into a mystery that spans archaeology, psychology, philosophy, and theology. The answer depends on how we define religion: is it the earliest burial ritual, the first pantheon of gods, or the oldest tradition still practiced today?

By tracing the origins of belief, we can begin to understand not only how religions began, but why humans continue to believe at all.

Before the Gods: The Prehistoric Mind

The earliest evidence of religious thought comes not from temples but from graves. Archaeologists have found burials dating back nearly 100, 000 years, such as those at Qafzeh Cave in Israel, where bodies were interred with ochre and grave goods, suggesting belief in an afterlife.

By the Upper Paleolithic, symbolic artifacts proliferated. The so-called Venus Figurines, small carvings of women with exaggerated features, appear across Europe and Asia between 35, 000 and 10, 000 years ago. The oldest known example, the Venus of Hohle Fels in Germany, dates to at least 35, 000 years ago and is considered one of the earliest works of figurative art.

Cave art at Lascaux and Altamira, with its haunting depictions of animals, is widely interpreted as ritualistic, perhaps tied to hunting magic or totemic belief. Then there is Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, a monumental complex built between 9600 and 8200 BCE. Its massive T-shaped pillars, some weighing up to 50 tons and carved with animals, predate agriculture and pottery. Scholars now argue that religion may have spurred the development of farming, not the other way around.

Together, these finds suggest that long before gods were named, humans were already ritualizing death, fertility, and the mysteries of nature.

The First Organized Religions

With the rise of cities came the first organized religions. In Sumer around 3500 BCE, the earliest written hymns and temple records appear. The Sumerians worshipped a pantheon of gods tied to natural forces and civic order, and their ziggurats served as stairways to the heavens. Surviving Sumerian texts include hymns, prayers, and myths, preserved on clay tablets in cuneiform script.

In Egypt, pharaohs were seen as divine kings, and elaborate funerary rituals culminated in the Book of the Dead, which mapped the soul’s journey into the afterlife. In the Indus Valley, seals and figurines suggest proto-Shiva figures, ritual bathing, and fertility cults that would later influence Hinduism. In China, Shang dynasty oracle bones reveal a system of ancestor worship and divination. In Mesoamerica, the Olmec and later the Maya and Aztec developed cosmologies centered on sacrifice, cyclical time, and divine kingship.

These early religions were not only spiritual systems but also political and social institutions. They legitimized rulers, organized economics, and provided shared narratives that bound communities together.

The Psychology of Belief

Why did religion emerge in the first place? Cognitive scientists argue that belief is rooted in the human mind’s tendency to detect agency. This “hyperactive agency detection” made it easy to imagine spirits in rivers, ancestors in dreams, or gods in thunder.

Religion also helped humans cope with mortality, offering continuity beyond death. It explained the unknown, giving order to chaos. It bound communities together through shared rituals, creating trust and cooperation beyond kinship ties. Anthropological studies suggest that belief in punitive, all-seeing deities encouraged fairness and cooperation in large, anonymous groups.

Neuroscience adds another layer. Brain scans show that religious experiences activate networks associated with emotion, memory, and self-reflection. Studies of praying nuns and meditating monks reveal increased activity in the frontal lobes (linked to focus and attention), producing a sense of transcendence. Other research shows that religious experiences active the brain’s reward circuits, the same ones triggered by sex, music, and drugs.

From Hymn to Scripture

The invention of writing transformed religion. Oral traditions became fixed in text, preserving myths, rituals, and laws across generations. In Mesopotamia, the Enuma Elish told of creation from chaos and the rise of Marduk. In Egypt, funerary texts guided souls through the afterlife.

In India, the Vedas (composed between 1500 and 800 BCE) codified hymns and rituals that would evolve into Hinduism, the world’s oldest living religion. The Upanishads (composed between 900 and 300 BCE) shifted focus from ritual sacrifice to philosophical inquiry, asking profound questions about the self and ultimate reality.

In Persia, Zoroaster’s hymns introduced a stark dualism between good and evil, influencing Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The Hebrew Bible reframed covenant and law as the foundation of a people’s identity, while later Christian and Islamic scriptures built upon and reinterpreted these traditions. Texts did not invent belief, but they stabilized it, allowing religions to expand across time and geography.

The Merging of Beliefs

Religions did not evolve in isolation. They collided, merged, and borrowed from one another. Greek gods became Roman gods; Egyptian Isis was worshipped in Rome; local spirits were rebranded as saints in Christianity. Animism never disappeared, it survives in indigenous traditions and folk practices worldwide, often blending seamlessly with major religions.

Flood myths, for example, appear across cultures: Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh, Noah in the Hebrew Bible, Manu in Hindu texts, and Deucalion in Greek mythology. These stories share striking similarities — divine punishment, survival of a chosen few, and renewal of humanity — suggesting either shared memory of ancient floods or archetypal human storytelling.

The great monotheisms — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — did not erase older beliefs but restructured them, embedding ancient rituals and archetypes within new theological frameworks.

Why We Still Believe

Today, neuroscientists can map the brain in prayer, and anthropologists can trace rituals across millennia. Yet the deeper question remains: why do humans still believe? Philosophers argue that religion persists because it addresses questions science cannot: meaning, morality, community, and identity. Psychologists note that belief offers resilience, community, and identity. Historians remind us that religion is not static but palimpsest, each layer written over the last, never fully erasing what came before.

The persistence of religion suggests that it fulfills needs that are not merely intellectual but existential. It is not only about gods but about being human.

The First Religion, The Last Question

So what was the first religion? If we mean the earliest spiritual practices, it was animism and shamanism in the Paleolithic. If we mean the first organized, documented religion, it was the temple cults of Sumer. If we mean the oldest still-practiced religion, it is Hinduism, with roots in the Vedic hymns.

But perhaps the better answer is that religion was never invented at all. It was discovered, again and again, whenever humans looked into the dark and decide that the dark was not empty. The story of the first faith is not about gods descending from the heavens. It is about humans, staring into the unknown, and choosing to believe that someone — or something — was listening.

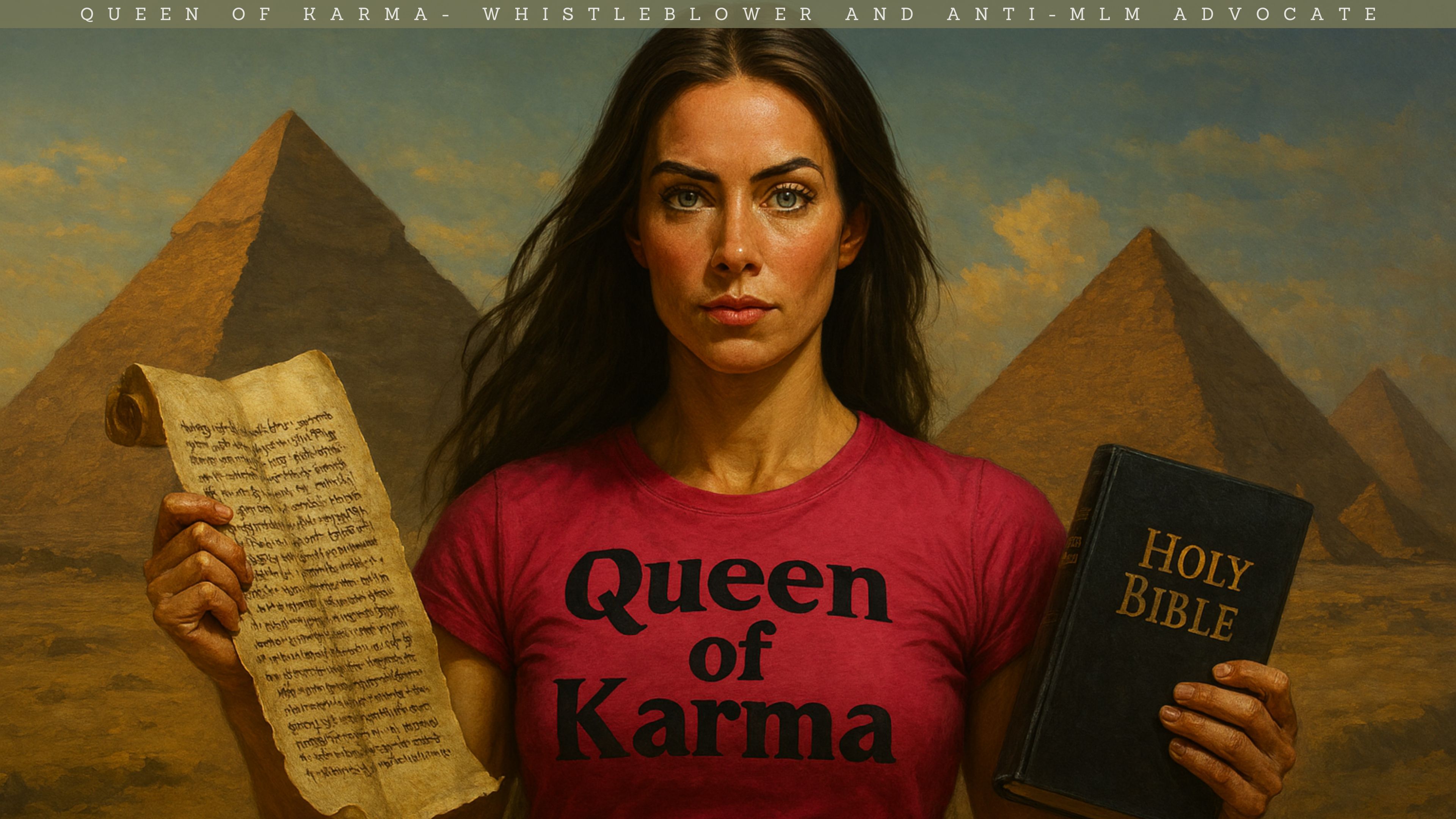

By Beth Gibbons (Queen of Karma)

Beth Gibbons, known publicly as Queen of Karma, is a whistleblower and anti-MLM advocate who shares her personal experiences of being manipulated and financially harmed by multi-level marketing schemes. She writes and speaks candidly about the emotional and psychological toll these so-called “business opportunities” take on vulnerable individuals, especially women. Beth positions herself as a survivor-turned-activist, exposing MLMs as commercial cults and highlighting the cult-like tactics used to recruit, control, and silence members.

She has contributed blogs and participated in video interviews under the name Queen of Karma, often blending personal storytelling with direct confrontation of scammy business models. Her work aligns closely with scam awareness efforts, and she’s part of a growing community of voices pushing back against MLM exploitation, gaslighting, and financial abuse.

Leave A Comment