Ascendra International claims to be a cutting-edge, ethical network marketing platform—but a closer look reveals recycled pyramid mechanics beneath the glossy façade.

Below, we unpack its origins, business model, and the red flags every anti-MLM advocate needs to know.

Overview

In June 2025, Ascendra International entered the Philippines‘ already-crowded multi-level marketing (MLM) scene with grand promises of “redefining network marketing.” Headquartered in Mandaluyong City, Metro Manila, Ascendra immediately positioned itself as a reformist alternative to the problematic status quo of Philippine MLMs. Its launch was spearheaded by four well-known industry insiders: CEO Engr. Jurgen Daniel Gonzales, Chief Strategy Officer Joseph Lim, COO Miko Imson, and CFO Francesca Fugen. Each executive brings a storied, and in some cases controversial, pedigree from the world of direct selling, especially from the notorious AIM Global (Alliance in Motion Global).

The company’s public mission, repeated across press releases and digital marketing, is to offer a values-driven, tech-forward business model with ethical leadership, “real business ownership,” and genuine income opportunities. While Ascendra’s narrative focuses on distancing itself from aggressive recruitment and “hype-first” tactics, both the structure of their business model and their compensation plan raise familiar—and deeply concerning—red flags endemic to so many MLMs.

Founders’ Backgrounds: AIM Global’s Legacy Rebooted

Ascendra’s leadership highlights are both its greatest asset and biggest liability. The four chief architects are veterans of AIM Global, where each gained immense experience, and notoriety, for their roles in building one of the Philippines’ most controversial MLMs.

- Engr. Jurgen Daniel Gonzales(CEO): Boasts thirty years in sales training and network marketing. Formerly AIM Global’s VP for Business Development, a central player in crafting its binary compensation plans and orchestrating regional expansions.

- Joseph Lim (CSO): “Hall of Fame” awardee at AIM Global; known for his visibility as both a lead recruiter and the face of several successful, but recruitment-heavy, MLM initiatives.

- Miko Imson (COO): Brings extensive operational and training experience from direct sales companies, including time spent as an in-house educator at AIM Global’s “AIMcademies.”

- Francesca Fugen (CFO): A self-described serial entrepreneur and advocate for women’s financial empowerment.

While these credentials sound impressive, they also solidify Ascendra’s model as a direct descendant of AIM Global’s playbook—but with a 2025 refresh: tech buzzwords, allusions to “real business ownership,” and a new digital platform overlay. Importantly, AIM Global, though massive in reach, is marred by repeated allegations of being a product-based pyramid scheme, investigated (and sometimes banned) in several jurisdictions. Both Jurgen Gonzales and Joseph Lim departed AIM Global only days apart in late May 2025, immediately preceding the launch of Ascendra—hardly a coincidence.

Business Model Analysis: Echoes of Recruitment-Driven MLMs

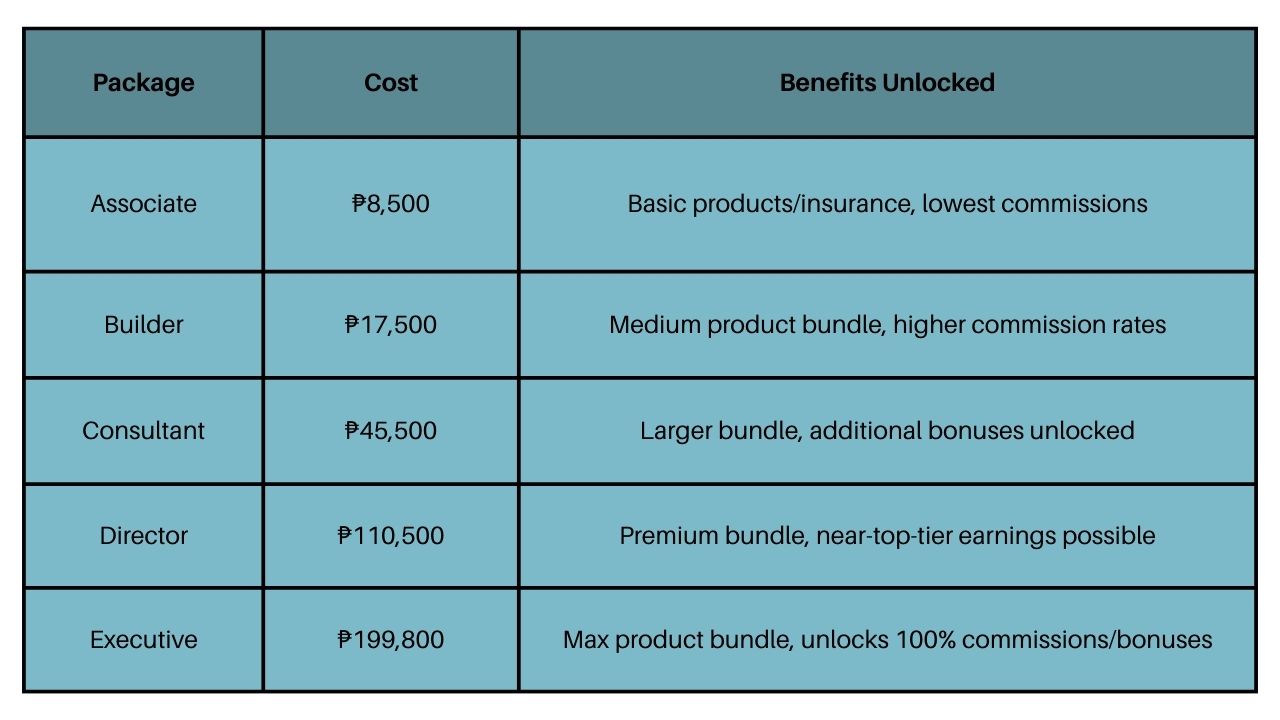

At its heart, Ascendra is a typical binary MLM, with all the classic trappings: enrollment packages, a multi-tier compensation structure, recurring auto-ships, and a business logic that heavily incentivizes recruitment over retail product sales. The “innovation” comes in the form of digital tools and an e-commerce dashboard for onboarding, but the fundamentals remain the same.

- Joining: Prospective members must purchase an enrollment package, ranging from the accessible “Associate” (₱8,500) to the “Executive” (₱199,800).

- Product Access: Packages bundle personal accident insurance (in partnership with Sterling Insurance), health supplements, and access to “Masterclass” digital training materials.

- Earnings: Income is derived from a mix of product sales, direct recruitment bonuses, binary team commissions, ‘unilevel’ overrides, and a multi-level “Lifestyle Fund” that unlocks luxury rewards—primarily for those who pay into higher tiers.

Ascendra’s one-account-for-life policy, AI tools, and explicit digital training are positioned as progressive differentiators. In reality, these measures do little to change the actual business mechanics: members advance and earn in direct relation to their package purchase and the successful recruitment of others into their downline.

On paper, Ascendra claims to lead with product value, not pure recruitment. This assertion rings hollow:

- Most packages bundle products and services that are already widely available—such as generic barley supplements, “Norwegian salmon oil,” and basic accident insurance—to create the veneer of value.

- The compensation plan is heavily “position-based.” Payouts, bonuses, and rebates are not primarily a function of product sales to outside customers, but of rank (determined by package spend) and downline recruitment.

- Many rewards (including luxury “Lifestyle Fund” prizes) are unattainable unless one upgrades to a high-ticket package and builds a substantial downline team.

This structural bias isn’t just theoretical: multiple anti-MLM critics, myself included, and independent reviewers flag Ascendra as prioritizing “forced upgrades, dead commissions,” and “inventory loading” at higher ranks, with a compensation system that’s profoundly tilted toward top spenders and recruiters.

Product Offerings: Generic, Overpriced, and Highly Saturated

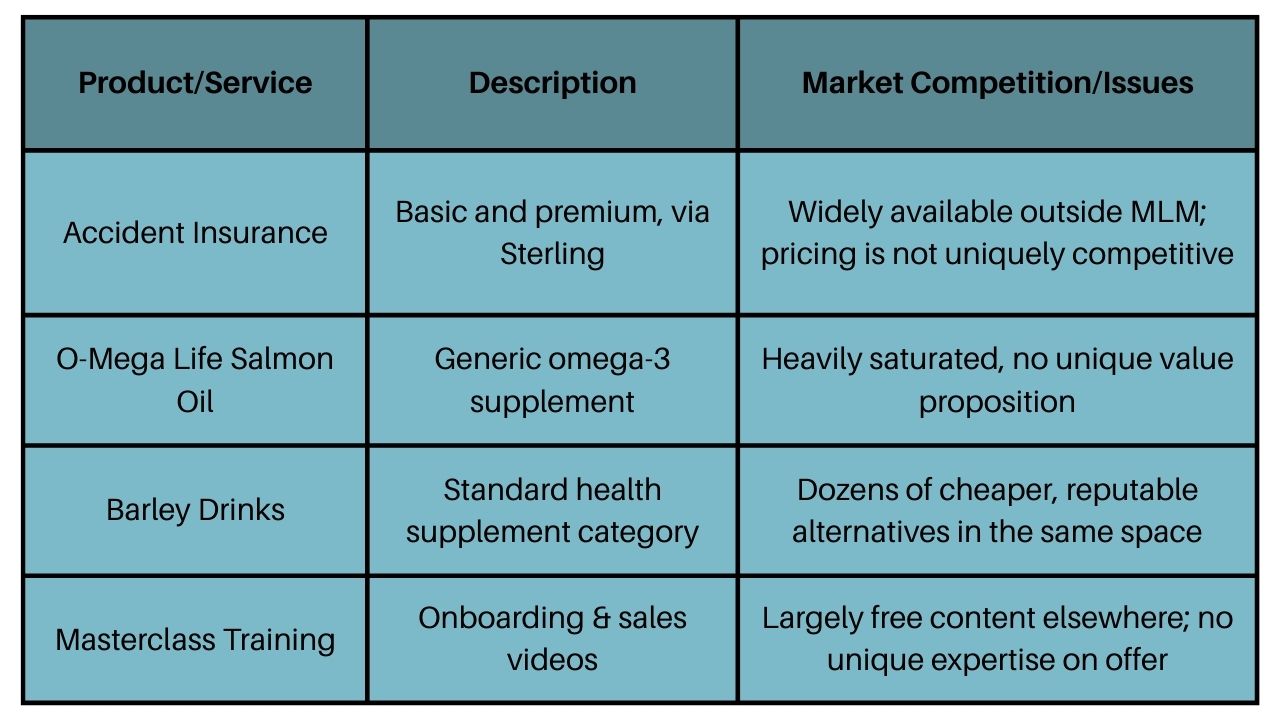

Ascendra’s product catalog includes three main verticals:

Personal Accident Insurance

- Basic (₱3,500/year): ₱750,000 death/disability, ₱250,000 for motorcycle accidents, ₱50,000 in hospital reimbursements, ₱25,000 burial, ₱125,000 murder/assault, ₱500/day for hospitalization (10 days), and unlimited 24/7 tele-consultations.

- Premium (₱5,000/year): Scales all above numbers, offering ₱1.5 million for main accident benefits.

The insurance policies are delivered by email, underwritten by Sterling Insurance. Ascendra is not itself an accredited insurer. The company acts more as a reseller or aggregator of group policies than as a traditional insurance carrier, and no license is required to sell these through the MLM system. - Market Assessment: Personal accident insurance is not in itself unique, and Ascendra’s plans largely mirror entry-level offerings available directly from many established Philippine insurers—often at lower price points or with more flexible coverage terms. The “hassle-free, no-medical-exam” pitch is standard for microinsurance in the Philippines, and the additional telemedicine benefit is now commonplace, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wellness Products

- O-Mega Life (Norwegian Salmon Oil): A generic omega-3 supplement, competing with regional and global brands such as USANA, AIM Global’s own supplement lines, Atomy, DXN, and Sante Barley.

- Barley Fusion (Korean Antioxidant Drink) and Best Barley (Australian Barley): Competing directly with nearly every established MLM and direct seller in the region, including Sante Barley, Edmark, I Am Worldwide, and more.

- Market Assessment: There is zero product differentiation here. All three supplement categories are commoditized, with significant price competition at both the retail and MLM level. Critics point out that virtually no one outside the Ascendra system would pay the “retail” price for these items—creating a situation where distributors become the main, if not the only, significant consumers (“garage qualifying” or “internal consumption”). This is a textbook marker for pyramid-style revenue structures.

These are bundled digital training packages and online resources, marketed as practical business and sales training for new recruits. Their market value is highly questionable, with similar resources widely available online for free or at drastically lower cost.

Summary Table: Key Product Offerings:

In-Depth Analysis: Ascendra’s products offer no compelling reason—in terms of price, scientific backing, or customer demand—to choose them over myriad non-MLM alternatives. The primary “customers” are the distributors themselves, raising profound sustainability concerns and regulatory red flags.

Objectively, Ascendra’s products do not compete successfully outside the walled garden of its MLM ecosystem. Omega-3 supplements, barley drinks, and accident micro-insurance are universal, mass-market items in the Philippines—and at the price points and margins offered by Ascendra, external demand is limited to zero.

Comparative Market Analysis:

- Omega-3/Fish Oils: Major brands (e.g., USANA, Herbalife, non-MLM generics) offer similar or superior formulations at competitive or lower prices. The vast array of health food stores and drugstores makes MLM “exclusivity” moot.

- Barley Supplements: The market is flooded, with brands like Sante Barley, I Am Worldwide, and Edmark dominating shelf space and enjoying established retail trust.

- Micro-Insurance: Local insurance firms and digital-first fintechs provide similar group policies, often with lower fees and more flexible terms. Ascendra’s main “innovation” is to package insurance as part of an MLM bundle, not as an insurance or fintech startup.

These are not breakthrough products, merely commodities wrapped in an MLM wrapper to justify ongoing monthly buys or higher joining fees.

Compensation Structure: “Pay to Play” and Position-Based Gatekeeping

To join Ascendra, members must purchase a starter package (“enrollment kit”), with options as follows:

The more you pay, the more you can earn—not because you are selling more, but because your earning potential is “unlocked” by your upfront spend. This “position-based” or “pay to play” mechanic is a classic characteristic of pyramid-style MLMs.

Income Streams are as follows:

- Direct Referral Bonus

Commission paid for personally enrolling new members. The rate escalates with your rank: bottom-rank Associates earn a fraction of the advertised “20%,” Executives get the full amount. If your direct recruit buys a higher-priced package than you have, your bonus is “dead”—passed up to your upline. - Unified Binary (Matching Bonus)

Standard binary MLM structure: each member recruits for their “left” and “right” leg, accumulating points or “BV” (binary value) for all purchases beneath them. Again, payouts are capped by member’s rank; an Associate might earn only a negligible fraction of an Executive’s bonus for the same team sales. - Unified Unilevel

Commissions are calculated as 10% of package or product purchases across 10 levels deep, but again these rates and eligibility are locked to your package tier. - Unified Override

Earn a cut (8–10%, tiered) of your downline’s binary and unilevel earnings—and only if at the relevant rank. - Ascendra Lifestyle Fund

Only the highest ranks, with substantial personal and team volume, become eligible for non-cash “lifestyle rewards” like gadgets, cars, luxury trips, and property—but only if they maintain high ongoing purchases and recruitment activity.

This entire model is built around “qualifying to earn” by paying for higher positions rather than by delivering retail value to outside customers. Far from being an egalitarian opportunity, Ascendra’s plan mathematically predetermines that those who spend the most up front and recruit successfully—not those who successfully sell to end customers—will receive the lion’s share of income and rewards.

This structure is identical in form (if not in branding) to the pyramid-style plans flagged by anti-MLM advocates and regulators the world over. The direct tie between one’s initial spend and “income potential” (uncapped earnings, access to the full percentage of bonuses, eligibility for high-tier rewards) is a defining feature of illegal pyramid schemes in many jurisdictions, including the Philippines, US, and Canada.

Enrollment Packages: Investment or Disguised “Pay-In” Fees?

Enrollment in Ascendra is not a trivial buy-in. For a member to plausibly earn anything but the smallest bonuses, either major monthly investment is required or they must pressure new recruits into buying ever-larger (and costlier) packages. Reviewers highlight “forced upgrade pressure” and “dead commissions” as critical frustrations—those who can’t afford to upgrade lose money to their uplines, and there is relentless pressure to keep buying larger packages and pushing inventory.

- Key Points:

High Initial Capital Outlay: The difference between bottom and top packages is more than twentyfold. - Recurring Purchase Requirements: Monthly product purchases or “subscription maintenance” are required to keep commissions active and to climb the ranks.

- Inventory Loading: Executive-level members are incentivized (and in some cases required) to make large product buys to maintain qualification, risking product not easily resold (a practice banned in ethical direct sales but common in pyramids).

All of this serves to create a system where the vast majority of earnings are not tied to sales to external retail customers, but to continual recruitment and the “pay to qualify” churn within the system.

Legal and Regulatory Status: The Fine Line Between MLM and Pyramid Scheme

Under Republic Act No. 7394 (The Consumer Act of the Philippines) and the draft 2022 “Anti-Pyramiding Act,” any compensation plan where most profits derive from recruitment, not real product sales to end-users, is illegal.

Several Additional Criteria are used by authorities to distinguish legitimate MLMs from pyramids:

- Revenue is primarily from external product sales, not from purchasing programs or new-member fees.

- Inventory buy-backs and refund policies are available.

- There is a real, competitive market for the products at fair value.

- High-pressure “positioning” and “pay to qualify” are absent.

Ascendra says it is “legally registered” and operates “in compliance with Philippine law” which is a claim that, in the context of Philippine law, refers only to generic company registration, not an express consumer protection endorsement. The company’s insurance business relies on bundled sales of group policies purchased from Sterling Insurance, sidestepping direct insurance licensing requirements. At present, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) does maintain a “seal of legitimacy” program for MLM firms, but this is opt-in, not proof of meaningful regulatory vetting.

AIM Global—Ascendra’s mother company in both culture and executive DNA—has been banned or fined in several international markets for its business practices. Notably, AIM Global has faced regulatory action in Vanuatu, Pakistan, and Uganda, among others, for alleged pyramid or chain distribution schemes. That Philippine authorities have not yet acted against Ascendra or AIM Global is not a guarantee of legitimacy, but a reflection of the country’s historically piecemeal enforcement and the slow pace of legal action on MLM fraud.

Anti-MLM Legal Checklist:

- Is most compensation tied to real retail sales? No. Instead, sales are overwhelmingly internal to network participants.

- Does the system require large, up-front purchases for top earnings? Yes; income potential is tied to how much members spend when joining.

- Are “ranks” earned by sales volume, or purchased? In Ascendra’s case, ranks are bought, not earned; sales merely maintain access, but do not unlock new positions.

- Are there mandatory recurring purchases/inventory loading? Yes, to maintain bonuses and access to incentives.

By these metrics, Ascendra’s model is deeply problematic and fits many official criteria for a disguised pyramid scheme.

From an anti-MLM and consumer protection angle, Ascendra triggers nearly every classic warning sign:

- Position-Based Income: Steep up-front investment is required for meaningful earnings—all major bonus and override structures are locked behind costly “rank” upgrades.

- Recruitment Over Retail: The system functions most profitably when focused on signing up more participants at higher-cost packages, not from genuine product sales to outside customers.

- Pressure and Disadvantage for Low-Income Recruits: Members who can only afford lower-tier packages are structurally disadvantaged; they lose commissions, can never access maximum bonuses, and are implicitly encouraged to “invest more” if they wish to advance.

- Encouraged Inventory Loading: Especially at the Executive level, so-called “inventory loading” is easy, with members buying excess product merely to qualify for rank or bonuses.

- Lifestyle Fund Gating: Non-cash rewards (cars, travel, property) are tightly linked to paid-for ranks, rather than sales achievement, creating shell games where only the highest buyers and top recruiters qualify.

- Lack of Transparency: The actual breakdown of sales vs. recruitment profits, retail sales volume, and income distribution among participants is not disclosed publicly; prospects are asked to “trust” ethical leadership without meaningful proof.

Critically, these issues are not small oversights—they are central to Ascendra’s “success” formula and represent the most predatory and misleading aspects of the MLM industry at large.

Executive Ties to AIM Global: History Repeats?

Given their high-profile departures and immediate joint re-appearance at Ascendra, it is clear that Ascendra’s founders have simply built a new vehicle using the core AIM Global playbook, hoping to ride the next MLM boom in the Philippines. The narrative of “rebirth” or “fixing the industry” cannot be separated from the very system these leaders helped establish and profit from previously. The anti-MLM community has repeatedly noted that new launches by ex-leadership are almost always attempts to relaunch the same business model with minimal variation—except for branding and rank structure—and that true reform is rare to nonexistent in these circumstances.

Industry blogs, press releases, and direct marketing outlets position Ascendra as the vanguard of a “values-driven evolution” of network marketing: “ethical business practices,” “AI-powered tools,” and “empowering business ownership” are recurring refrains.

However, the anti-MLM community is not fooled: BehindMLM and Neil Yanto (among other reviewers) have issued scathing, detailed breakdowns of Ascendra’s plan, warning would-be recruits. Consumer watchdogs and legal analysts argue that the blizzard of corporate branding and “digital innovation” fails to address the root ethical issues of the business: the majority will lose money, top recruiters and package-buyers collect the spoils, and the risk of legal action is ever-present.

Ascendra’s future—like all recruitment-driven MLMs—is mathematically and structurally unsustainable. Unless Ascendra makes genuine changes—rewarding sales to external customers, lowering entry barriers, and capping or eliminating “pay to play”—its fate will mirror that of the hundreds of MLMs before it: initial boom, an explosion of internal recruitment and hope, followed by an inevitable collapse leaving the majority in the red.

Effective anti-MLM advocacy requires exposing the structural truths beneath the branding, documenting real-world losses, and lobbying hard for law that criminalizes “pay to play” and locks rewards to external, customer-based sales. Ascendra’s story is not unique, but it is especially egregious given its founders’ history and transparent “values-washing” of old, unethical business tricks.

A Necessary Deep Dive, A Necessary Warning

Ascendra International promises to “rewrite the playbook” of Philippine network marketing. Instead, it delivers the same old pyramid, just with better branding and fancier tech. Its structure, incentives, and leadership boom in every market where regulatory enforcement is slow and social vulnerability is high. Ascendra’s arrival is both a threat and an opportunity: a threat to the next wave of hopeful Filipino entrepreneurs who may unknowingly bankroll the next pyramid; an opportunity for anti-MLM advocates to shine a light on its mechanics and accelerate the campaign for genuine reform.

Everyone considering joining Ascendra—or any new MLM—should ask: Would I buy or recommend these products outside the network? Are rewards tied to customer sales, or only to recruitment and package spending? What happens when recruitment slows? In Ascendra’s case, the answers are clear—and deeply concerning.

By Beth Gibbons (Queen of Karma)

Beth Gibbons, known publicly as Queen of Karma, is a whistleblower and anti-MLM advocate who shares her personal experiences of being manipulated and financially harmed by multi-level marketing schemes. She writes and speaks candidly about the emotional and psychological toll these so-called “business opportunities” take on vulnerable individuals, especially women. Beth positions herself as a survivor-turned-activist, exposing MLMs as commercial cults and highlighting the cult-like tactics used to recruit, control, and silence members.

She has contributed blogs and participated in video interviews under the name Queen of Karma, often blending personal storytelling with direct confrontation of scammy business models. Her work aligns closely with scam awareness efforts, and she’s part of a growing community of voices pushing back against MLM exploitation, gaslighting, and financial abuse.

Leave A Comment